The Psychedelic Light of Saint Alicia

Remembering the Harvard psychedelic leader who gave it up to be a Friend.

Listen to this on Spotify, iTunes, YouTube, and most podcast feeds.

Sometimes, people run away from the light. They feel they don't want to know what is right, for fear it should turn out to be something too hard for them to do. Perhaps they have read something, or listened to somebody who has strong ideas of his own about what is right, and for fear of being controlled, they shut their minds against the questions that have been raised. This is not a very satisfactory solution, because the questions keep nagging in the back of your head.

It is much better to sit down quietly and wait in the light that is always shining.

Licia Kuenning, “The Light of Christ”

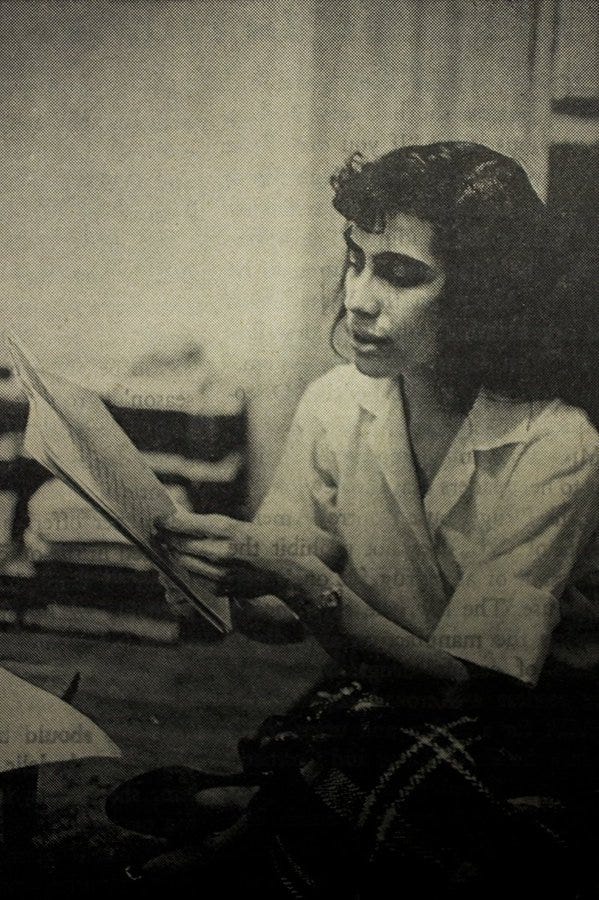

A couple of months ago, my friend Paul told me about a lesser-known psychedelic figure from the legendary Harvard ’60s. Immediately I fell in love; coming across this hero’s candid writing was no small part of finding the inspiration to start this newsletter, and I had long been planning to profile her. In tragic providence, I learned that she passed away just a few weeks ago as I was writing about her, discovering a lovely obituary by her husband Larry.

Her name was Alicia Kuenning, or Licia, known in the ‘60s as Lisa Bieberman.1 Her tenure in psychedelia was a true embodiment of integrity. If there are such things as psychedelic saints, she would be one—though I imagine she would hate this label, for most of her life was spent outside of psychedelia. May peace be with her and her family, and may her spirit echo on long after her life of devoted love.

While known by her religious community and psychedelic historians, her story and perspective are rarely told among psychedelic laypeople. After penning a powerful essay in the late ‘60s (presented at the bottom of this piece), her husband says she attempted to work out a theology that was simultaneously Quaker, Christian, and psychedelic. After leaving psychedelics behind in 1971, she would spend her remaining years devoted to preserving Quaker history, writing essays about understanding its past. In learning more about her, I found her meditations on Quaker history to be just as applicable to psychedelic history or any tradition we care about:

Quakerism is a fascinating historical phenomenon. I myself often don't know what to make of it as regards how some of what Friends of the past believed and wrote applies to my own life. But I want to know the truth about what they were, and I want other Friends to know the truth about it. There is no integrity, and no education, in creating false images of the early Friends and then holding them up as models.

Licia Kuenning, “Publishing Old Quaker Texts”

While Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert (Ram Dass) are mentioned in every recap of the ’60s Harvard psychedelic scene, the name Lisa Bieberman is absent from most (though not all). Despite her relative obscurity, she was very much a leader, working for Leary’s International Federation for Internal Freedom (IFIF). She produced a variety of community resources from the Psychedelic Telephone Directory, to the one-woman Psychedelic Information Center bulletin run out of her apartment, to harm reduction materials and tripping guides. And like a true psychedelic leader, she got busted for spreading the psychedelic gospel in sugar cubes.

After trading some emails, her husband told me that he is working on transcribing her autobiography, To Mark a Spot: A Psychedelic Pilgrimage about her nine years in the psychedelic movement. It will be released sometime in the next couple of years and will share much more of her story.

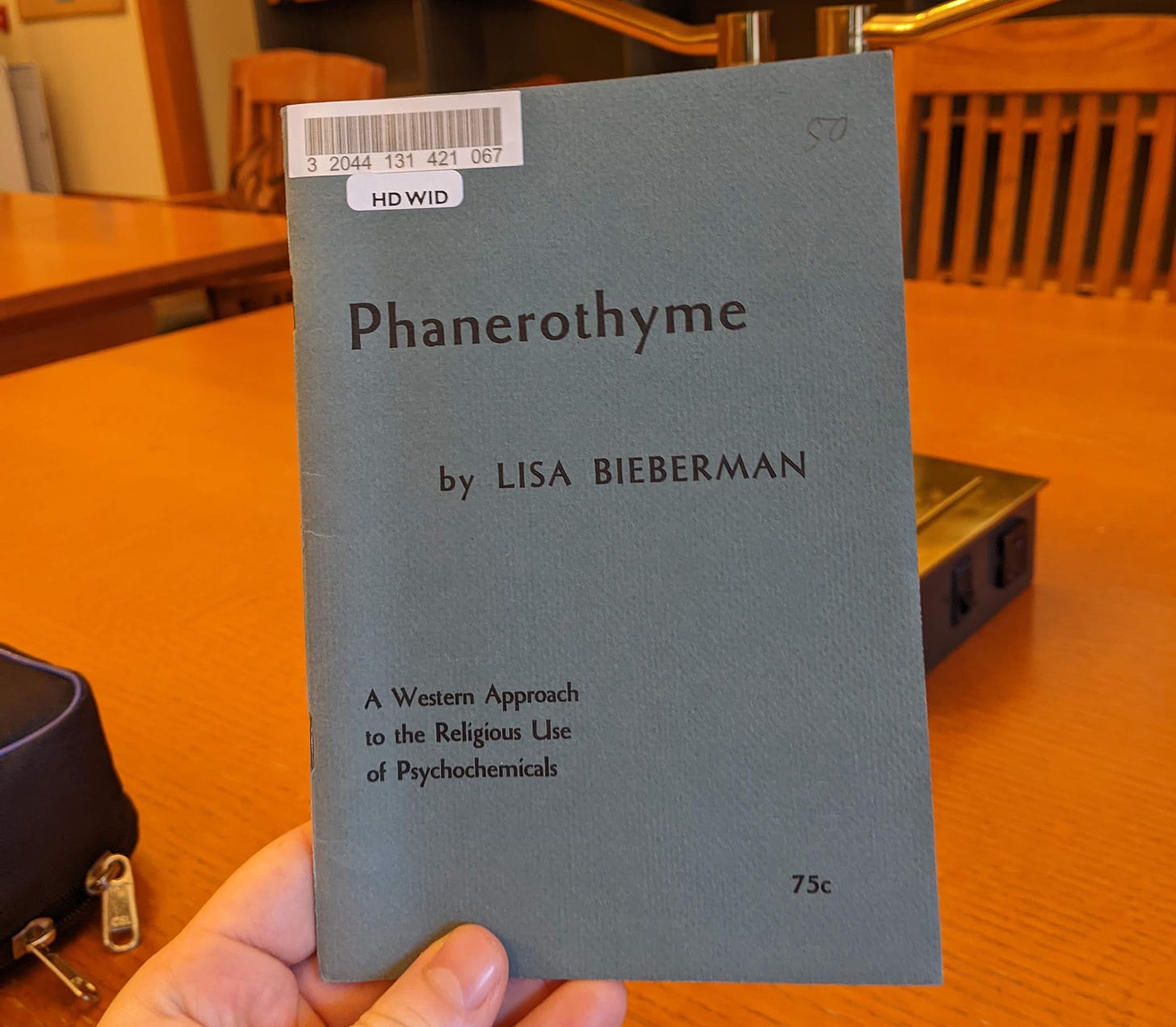

Phanerothyme Theology

The world is real;

The God who created it is alive, and will stay that way.

Lisa Bieberman, “Phanerothyme”

Kuenning was more than just a community builder, harm reductionist, or resource provider. She was a spiritual leader, taking a thoughtful religious approach to psychedelics that was counter-countercultural. As detailed in her essay, “Phanerothyme: a Western Approach to the Religious Use of Psychochemicals,” Bieberman understood her experience in radically different terms than the psychedelic mainstream. She was not afraid to make critical judgments over more “destructive” approaches to psychedelics that “cannot be maintained over any length of time, however intellectually appealing they may be at the moment they are propounded.”2

In what would be some of her last public words on psychedelics,3 Bieberman argues for a structured, Quaker-style minimalistic setting. Attempting to come up with a new vocabulary for a new approach, she defines “phanerothyme”—a term coined by Aldous Huxley to be a synonymous competitor to Humphrey Osmond's more popular “psychedelic”—as a method that seeks mental and spiritual clarity:

Call “psychedelic” what you will, but by phanerothyme shall be meant only those substances to the use of which a sober religious purpose is appropriate, those substances of which the occasions of ingestion mark milestones in one's life, to which one looks long after the event for encouragement and faith…The test is not how magnificent the visions, but rather how clear is the understanding obtained, and the test of clarity is its applicability to the decisions of daily life.4

Her theoretical approach should be compelling to psychedelically-curious Christians, if too optimistic in hindsight. While her thoughts are far more grounded than her contemporaries, the ‘60s version of Bieberman underestimated the potential long-term side effects of regular psychedelic use.

There is another fascinating chapter of her psychedelic odyssey that’s even less covered by psychedelic historians: correspondence with the Catholic monk Thomas Merton.

Silent Pen Pals

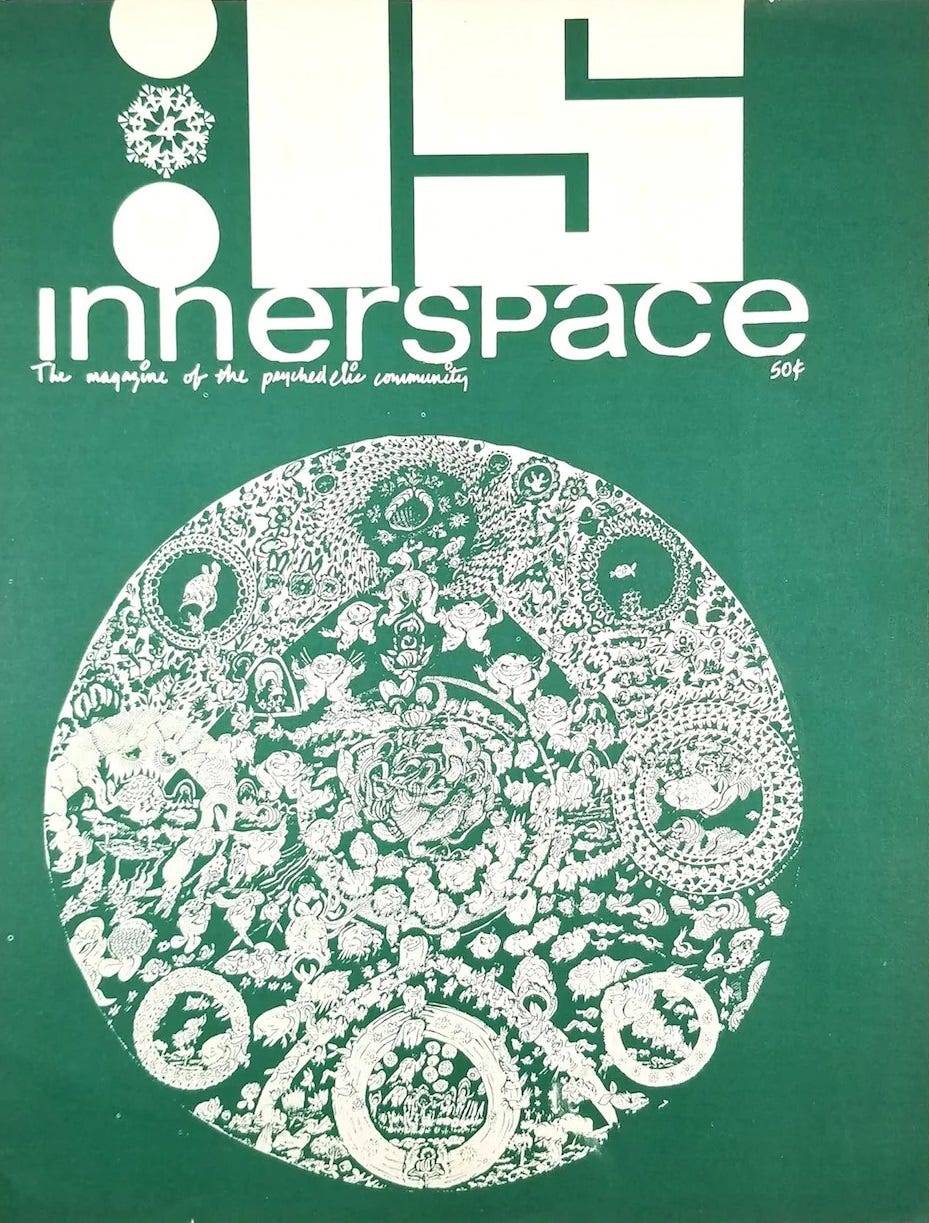

Before “Phanerothyme,” Bieberman wrote, “On Getting the Message” for a short-lived psychedelic magazine called Innerspace, which Merton somehow obtained. In the piece, she discusses the difficulty of communicating the psychedelic experience. Merton was a world-famous monk who was inundated with letters, spending much of his monastic vocation responding to questions about interfaith spirituality, politics, and life. On the topic of psychedelics, he had only ever expressed skepticism at best. But he was so struck by her piece that he took the time to write her an unsolicited letter. Here is an excerpt5:

The problem of experience and communication, solitude and community, is something I have grappled with for a very long time. It is true one must communicate. But it is most important also not to communicate in words, sometimes, and above all not to be anxious to communicate, not to be anxious to be understood, not to be justified, not to be accepted necessarily. And so on. You know what I mean. I honestly think you people need more than anything else a disciplina arcani (like the first Christians—they did not talk about the sacraments). You need to get a good sane group of you underground fast, because with the public emotion and fury about it this whole thing may dissolve fast into something it need not be. You all strike me as lovely innocent people who may suddenly find that all hell has been let loose, and believe me the establishment in this country has developed that to a high pitch of perfection. I know of course this is a sort of charismatic thing like that in the fourteenth century, and no one can keep it underground or even want to. But I think you should have that too. I think you really need an element of silence, of loneliness, of non-communication in order to make the whole thing more valid and keep it so.

April 15, 19676

Merton’s full letter, published in the anthology The Road to Joy, shows a level of compassion for her psychedelic optimism. This sharply differed from the monk’s usual psychedelic views, which were becoming partially influenced by his growing interest in Indigenous spirituality.

But four months later, Bieberman’s patience with the psychedelic scene had run out, and within a few years, she would quit drug use altogether.

A Friendly Life

While this ended the most public portion of her life, it was only a sliver of her entire humanity. Her faith journey continued on, marrying and changing her name to Licia Kuenning, starting a new Quaker community and publishing house with her husband. It was not always easy between her and other Quakers, known as Friends, because the Kuennings were looking for a Quaker-style Christian community—truer to the Quaker past—that was at odds with contemporary organized Quakerism. This culminated in her eventual declaration that in the year 2006, the Biblically-prophesied New Jerusalem would arrive in Farmington, Maine.7

But even in her mistakes, she displayed her virtues, as one Maine local noted:

[She] stood up on the stairs of the bandstand and acknowledged that nothing had happened, that she’d been wrong, at least about the date. I admired her for that—admired her a great deal—because a lot of prophets would have slunk off, never to be seen again. And people around town were pretty forgiving, too. She was only human, after all, and the prediction hadn’t caused the slightest harm to anyone.

While such grace in error is admirable, far more important than what she got wrong was what she got right. As noted in her obituary, “Licia was always marked by single-minded devotion to what she believed in, even though her beliefs changed over the course of her life.” Coming from this stranger in shared geography but a distant psychedelic land, I find her devotion to show a clarity of heart—a truly phanerothyme soul. Well done, good and faithful servant.8

So yes, if there were a psychedelic canonization process, I would first nominate Saint Alicia for performing the miracle of psychedelic integrity. But I have no doubt she would hate this name. Licia was a unique Christian who wanted a community like the Quakers of the past; she was not a Saint, just an old-school Friend.

But I must confess that, no matter how much I quote her, this piece is not a proper tribute. In fact, the more I excerpt her, the more I disobey her wishes about how we remember figures of the past, which I only discovered as I was finishing up this piece:

Read whole documents rather than excerpts or condensed versions… Remember that those who excerpt documents have an agenda: what they leave out is what does not suit their agenda. It might nevertheless be important for understanding the document….I do not say to Friends that if they study the Quaker past they will learn how to recreate it. The seventeenth century will not come again. I have the more modest hope that we will learn to tell the truth about it.

Licia Kuennig, “Understanding the Quaker Past”

Between my selective use of her and Merton’s words, I feel properly called out.

I must confess my agenda was to honor her as a figure of remarkable psychonautic integrity. But in the challenge of her words, she gently reminds me that she was more than a psychedelic hero or a Christian Quaker communitarian, more than Lisa Bieberman or Alicia Kuenning. There is just too much of her that has been left out.

I hope at least one person reading this honors Alicia by reading her full pieces, straight from the source. Her words are far more provoking beyond their psychedelic, Christian, or Quaker contexts, and they remain in the present tense because the Light keeps shining through them. She challenges us to think about why we tell the truth about what we love, bounded by the limits of our sources, our attention, our biases, and our aims.

Perhaps any excerpts we make of any of our heroes cannot help but diminish them in the name of our agendas. Perhaps the best we can do is fess up to it. And perhaps we can forgive ourselves for our own self-diminishment, for anything we write is only a small excerpt of our total thought. Any story we tell about ourselves is just a curation to be used, hopefully for the good of someone else. And we—even in our fullest, truest selves—are only an excerpt of the Light.

Given her departed wisdom, it is only proper that I let her have the last word through a full republication of her original essay in The New Republic, August 5, 1967. It is a piece of Light as relevant as ever.

And even though I improperly labeled her a psychedelic saint for my own purposes, I hope she can forgive me for lifting her up as a psychedelic role model. But I don’t think she would want to be primarily remembered this way.

So let me just say thank you, Licia, for being a Friend.

The Psychedelic Experience

Lisa Bieberman ● August 5, 1967

It was five years ago that I attached myself to the Cambridge group that started the psychedelic movement. In those days we didn’t use the word “psychedelic” much — the accepted phrase was “consciousness-expanding drugs,” or more briefly, “mushroom,” since the Harvard group worked mainly with psilocybin. There was a whole new world in the mushroom, so we said — the key to a stronger, richer human life soon to be made available to every man. We were full of the happy excitement of sharing a soon-to-be-public secret that was going to save the world.

Were we like today’s novice acidheads? It is hard for me to tell, because my perspective has changed so much. To my younger, more naive eyes, the mushroom people were idealistic as children, brave as Christian martyrs, and full of wisdom. They were an indissoluble family, destined to go forward, hand in hand, to win souls and bring in the Kingdom.

I have no idea what has become of most of them. They are not in the movement any more. Some of the conservative fringe members are still conservative fringe members. Some went “straight.” A few drifted away from psychedelics to follow Meher Baba or embrace some other form of occultism. The originally most enthusiastic members just disappeared, sometimes turning up briefly in this city or that, but no longer activists. The leaders, Leary, Alpert and Metzner, apparently unmoved by the fact that their own group had fallen apart, went out to preach LSD as the key to consciousness-expansion, to new starry-eyed kids, forming new groups that fell apart in turn.

Two years ago I started a bimonthly newsletter called the Psychedelic Information Center (PIC) Bulletin, in which I reported the activities of various projects purportedly aimed at furthering the use of psychedelics for religious or philosophical purposes. The collected back issues are a catalogue of frauds and failures. I finally had to change my editorial policy, because I came to realize that I did readers a disservice to report on things like the Neo-American Church, the League for Spiritual Discovery, the psychedelic shops and so on, as if they were to be taken seriously. Most of the psychedelic projects I reported have flopped, even though the more obvious losers were screened out before printing. Those that remain are a caricature of the psychedelic vision, a mockery of the idealism of youth. (The Church of the Awakening, run by John Aiken, is an exception. It is led by older people who mean what they say.) If the utopian vision of 1962 was too good to be true, it does not follow that what came out of that had to be this bad.

Does the psychedelic experience really have to be offered to the public in the form of bizarre shows? Do the psychedelic people have to live in squalid ghettos? Does their conversation have to be a rapid-fire rap of slogans and meaningless declarations of “love”? Does LSD still have to be used so excessively and so carelessly; do freakouts have to be regular occurrences at Millbrook (Leary’s Mecca)? Do interpersonal relationships among acidheads have to be so shallow, so short lived? Must the leaders deliberately foster distrust between age groups? Do cheating and stealing have to be the rule among acid dealers?

The word “psychedelic” is ruined; it might as well be scrapped by those who still wish to speak earnestly about their experience. Psychedelic now means gaudy illegible posters, gaudy unreadable tabloids, loud parties and anything paisley, crowded noisy discotheques, trinket shops and the slum districts that patronize them. There was something I used to mean by psychedelic but if those posters are psychedelic, that other thing isn’t. Put “psychedelic” down along with “community,” “love,” “religion” and other good words the hippies, with the help of Leary & Co., have corrupted. (A community is a place for people to live and work together, put down roots, raise their children and grow old. There is no psychedelic community, least of all at Millbrook, a madhouse place that nobody can stand for long. Of the group that started there, none remain except Leary and his daughter and son. In the mad scramble to be In, nobody asks what became of the people who were In last year, and the latter are silent. How long can this farce be played out? Apparently indefinitely; the turnover of Leary’s followers goes on, each new group of converts as true-believing as the last, until their turn comes to fall out through divorce, rejection, psychosis or disillusionment.)

Whatever happened to the Neo-American Church Boo-Hoos whose names I used to publish (and what will happen to the new ones)? Art Kleps, “your Chief Boo-Hoo,” went to Florida where he knew there was a warrant for his arrest, got raging drunk, picked a fight with his ex-wife and passed out in a railroad station where he was picked up by police and, when his identity was learned, held on the old charge. (This is what he means when he writes in his recent bulletin, “This is not a good test case — too messy.”) I made the mistake of feeling sorry for him and raised $1,000 for his bail, only to have him retreat into Millbrook and refuse to appear for trial, thus causing me to lose most or possibly all of the bail money. He is able to get away with this because psychedelic people have such short memories, and because they apparently do not expect their leaders to be trustworthy.

Not the least consequence of all this is the loss of the possibility of trust. A sensitive person can no longer distribute LSD after seeing how it is to be used. One can no longer buy LSD; the dealers cannot be trusted. It is unlikely that I will ever go anybody's bail again. No old head expects much of any newly announced psychedelic project (unless it goes commercial, and then it may become big and rich, but irrelevant).

Younger converts, however, may be taken in rather cruelly. Last winter a college freshman in Kansas, having been appointed Neo-American Boo-Hoo for his campus, publicized his appointment and began running LSD sessions for members. The church was soon infiltrated by federal agents, and the boy was arrested in the act of handing the sacrament to one of them. “Attaway to get busted, Jim,” wrote Kleps in one of his bulletins. But when the trial approached, Jim’s friends tried in vain to obtain from Kleps the membership applications of the entrapping agents, which were essential to the defense. They write: “We all tried repeatedly to get in touch with Art Kleps. The first phone call roused a secretary who didn’t know who he was but promised to leave a message ‘somewhere.’ The second call also had vague overtones, but we finally got a message for Kleps to send us the applications which the two narcotics agents had filled out during their sleuthing of Jim. The trial began, and still no membership cards showed up. We called again, and this time no one even answered the telephone. There was never any communication, no money, no support, help in any way. Tim Leary did send a cryptic note offering love and help, but little came of that. Jim was placed in the absurd position of having the money for his lawyer come from [those] he was trying to oppose, the Episcopal Church. (His father is a priest.)”

Let those be warned who think a fake church is better than none for testing the laws. In this sad letter, naiveté of distance still shows through the disillusionment, e.g., in the supposition that any of the female adornments of the Millbrook estate could be described as a “secretary,” and in the assumption that Art Kleps would even have wanted documents on file. In his mellower moods he has been observed to toss mail unread into the fire. The experience described is typical of what is to be expected in attempting to communicate with the estate at Millbrook (known as “Castalia” after Hesse, or maybe Kafka): the note from Leary is also typical. It is Leary’s custom to offer his disciples love and help on any occasion, and to mean absolutely nothing by it.

I have been told I shouldn't publish these things, because they will weaken the image of the psychedelic movement, and that any means are justified in popularizing LSD because it is the only thing that can prevent nuclear war. This silliness is part of the Psychedelic Line, the collection of half-truths, wishful thinking, and lies repeated until they are believed, that has the movement morally paralyzed. LSD had been sold out, and it’s up to anyone who still cares about, or remembers, the psychedelic experience to reject the phony, commercialized thing that has been erected in its name.

Vacant-faced kids drop by the Psychedelic Information Center and ask, “What’s happening?” Pressed for what they mean, they usually turn out to be looking for a rock band, or maybe a shop selling buttons, or news of the latest busts. I have nothing for them that they want, and they go away puzzled — they thought I had a Thing here, but it turns out to be just a few publications, no flashing lights, so it isn’t hip.

There’s still the same thing happening, of course, that’s been happening since psychedelics became available: the possibility of having an experience that will reawaken a person to the basic truths he understood as a child, and point the way to becoming a better man or woman. (But even this possibility is cut off for many of the kids — they have had 100 trips and are jaded. Thus the pathetic search for drugs “stronger than acid.”)

That would be the only psychedelic happening that I’d be interested in — if a few people could be helped to lead better lives with the aid of psychedelics. If the Indians can do it with peyote, it should be possible for us — if we could just get clear of the cultish, flashy, idiotic pseudo-underground.

I do have a plan for it, involving a house in the country, above ground where guided sessions will be run for small groups, by advance application. But it won’t go into effect until 1970, as it will take me that long to earn enough money and make adequate preparations and plans. I have seen too many psychedelic projects fall apart to go into one of importance without considerable planning. I have been planning this for more than a year — but then there is no reason for anybody but me to believe that it will work. If another head told me he was going to do something like that, I would be skeptical. I believe it because it is my own commitment. I will not abandon the psychedelics, to which I owe my most valued experiences, to their present fate.

The LSD story up to now has been a tragedy. A tool of tremendous potential value for science, medicine and personal life enrichment has been allowed, partly by default, to become the plaything of unscrupulous cultists. Most of us have been too hypnotized by the increasing publicity attending the splashy hippy happenings to remember or assert that LSD was once thought to bear quite a different message. Whether one places the blame for its corruption on the politicians who drove LSD underground, on the academicians who allowed this to happen, or on the opportunists who took advantage of the result, the fact remains that society could hardly have done a more thorough job of confounding the good, and magnifying the evil potential in these powerful drugs if that had been the avowed intention of all concerned.

If the future of LSD is to be more wholesome than its past, it must be squarely recognized that the most publicized advocates of the psychedelic are its worst enemies. We cannot rely on them to fight our battles for us, whether it be for religious freedom, the right to do research, or the dissemination of accurate information. Flower power is no substitute for integrity.

I will refer to her as Bieberman in reference to her ‘60s writing.

P. 4-5

While undated, according to Luminist this was published in 1968. Apart from “Phanerothyme,” the last psychedelic words I could find of Bieberman’s would be a 1970 speech to Wilmington College in Ohio, “What is God Doing with Drugs,” which some lucky eBay auctioneer snagged a few years ago.

Bieberman, Lisa, “Phanerothyme: a Western Approach to the Religious Use of Psychochemicals,” p11-12

This whole interaction shows a new side of Merton’s psychedelic thought which I will further interrogate. Bieberman’s response to Merton is unpublished, but I hope to visit the Merton archives this year and find it.

Merton, Thomas, The Road to Joy, p. 351-2

Matthew 25:23